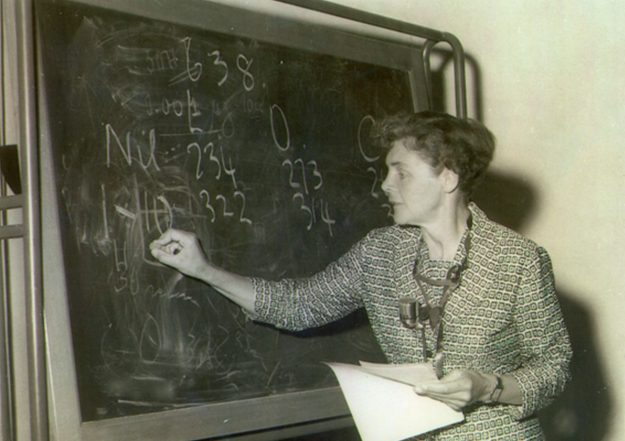

How prepared are you to be wrong?We are told all the time that the very best teachers are lifelong learners who are always willing to take risk to deepen their understanding of the world around them. But what does this really mean? What does taking a risk actually look like when it comes to continuing to grow, learn, and develop our practice? How do we justify the philosophies and theories that we hold? In what ways do the approaches we use change to reflect continued learning and growth? In deepening our teaching and/or leadership practice, are we willing to ask the hard questions that it takes to push us forward? In a great Ted Talk, Margaret Heffernan shares some research that suggests that we are hard wired to organize ourselves and our learning by surrounding ourselves with people and information that reinforces our own opinions rather than challenging them. Margaret believes it is essential to align ourselves with people who are not just echo chambers telling us what we want to hear, but to actively seek opposition. To illustrate this point, she shares the story of an amazing physician named Dr. Alice Mary Stuart, who was also known as the ‘woman who knew too much’. I first heard about this story from my friend Marina Gijzen, the elementary principal at the Nanjing International School. I revisited this story recently as I have been exploring what good leadership means. Alice was a physician and epidemiologist specialising in social medicine and the effects of radiation on health. She identified a major problem in the 1950s when she noticed that the incidence of childhood cancers were beginning to spike. Upon looking at the statistics, she observed that this spike was indeed a reality and made it her life’s work to figure out what was happening. She painstakingly created survey after survey interviewing the parents of children who were stricken with cancer in an effort to determine the root cause. She interviewed countless mothers in detail over a period of several years and although she did not really know what she was looking for, something glaringly obvious popped out at her during her investigation. She was able to determine that mothers of children who had died from cancer had had x-rays taken of them during their pregnancy. This was the 1950s and the x-ray machine was a major technological breakthrough. The medical professional was celebrating this new invention and Dr. Alice's finding flew in the face of conventional wisdom at the time. Nobody wanted to know this information and X-rays continued on, so Dr. Alice embarked on 25 years of continued research to further address this problem in an attempt to ban the X-raying of pregnant women. To prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that it was these x-ray machines that were the root cause of the spike in childhood cancers, she had to align herself with people who would challenge her theory…. Enter Dr. George Kneale.

Alice actively sought out someone who was completely different than her in every way imaginable. Dr. George was a statistician and numbers cruncher who was extremely introverted which was in stark contrast to the extraverted Alice. He was a recluse who preferred numbers over people. She hired him so that his number one job was to actively disconfirm her findings and to disprove her models of work. She demanded that he find her wrong because this was the only way that she could refine her work to the point that she had the evidence that she needed to move forward and convince the medical profession of the damage being caused by the x-rays. It was through this very unique partnership that both Alice and George deeply developed their understanding of the work that they do and after 25 years, through great turbulence and conflict, Alice had resounding proof that the X-rays being given to woman during their pregnancies was the root cause of these childhood cancers. It was in the 1970s that the UK government finally listened and made it law that women could no longer be X-rayed during their pregnancies ultimately putting a stop to childhood cancers related to radiation exposure while in utero. The main reason for this was the collaboration between Dr. Alice Stuart and Dr. George Kneale, despite their very different viewpoints and perspectives. I share this story because the lessons learned from the Alice Mary Stuart story are so applicable to our growth as teachers and leaders. It is very easy to fall into the trap of routine and methodical thinking about what we feel is right. Whether it be teaching students in the classroom or being a leader within an organization, our views, opinions, theories, and ideas are not bullet proof. In an effort to refine our approach and better understand why we do what we do, we must remain open to being wrong. Our continued growth is dependent upon having a sound structure to the way we collaborate in regards to the work that we do. We must continually strengthen our capacity to develop relationships with people that are very different than us, especially when it comes to challenging the beliefs we hold about the work that we do. And when we find that we’ve made mistakes and that perhaps some of the approaches/ideas that we are putting into practice are wrong, we need to accept these moments as holding the insight needed to help make the change necessary for continued growth and learning. When I look at my own work, I put a massive emphasis on the power of reflection and addressing the affective domain whenever possible with the students that I teach and the educators that I train. I cannot blindly accept that my way is right, but must challenge myself, and connect with others who will challenge the work I do. I’ve had great discussions recently with a number of researchers/practitioners who continue to challenge the beliefs that I hold and the approaches that I use. And I too challenge them to better understand their work. It’s the insight gained from these exchanges that helps me to assess how accurate my own views are and the next steps needed for me to change what I do in order to better my own practice. I’d like you to reflect on who you surround yourselves with and the role that these people play in helping you to become better at what you do. How often is your work challenged? How do you accept these challenges? How have these challenges helped you to better your best and continue to deepen the work that you do? Care to share? Please comment below! Thanks for reading.

3 Comments

Hi Andy, I agree it's important to have critical friends that challenge your thinking and widen your horizons. But a "critical friend" has to be trusted to be "critical" (in the objective, constructive way) and a "friend" (someone who attacks the problem, not the person). Too often criticism is mistaken for feedback and the end result is that you become less of a risk taker - not wanting to take the hits for your ideas any more. I find the critical friend relationship really only exists in face to face environments (online and in person) as the human interface is a key feature for it to work. Happy clapping or trolling in 140 characters are equally useless and destructive to a systematic approach to improvement, in my humble opinion.

Reply

Bobby

2/5/2016 04:07:41 am

Great stuff!

Reply

Tracy Fleming

4/18/2016 08:24:40 pm

Is there an email address I can contact you at? I am helping our PE teacher create a planner during our first year of pre-authorization and I have some questions you seem to be very knowledgable of. Thank you!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorKAUST Faculty, Pedagogical Coach. Presenter & Workshop Leader.IB Educator. #RunYourLife podcast host. Archives

September 2022

|

- Welcome

- All Things Teaching and Learning

- The Aligned Leader Blog

- Consulting and Coaching Opportunities

- My TED X Talk

- My Leadership Blog

- Run Your Life Podcast Series

- How PYP PE with Andy Has Helped Others

- Good Teaching is L.I.F.E

- The Sportfolio

- Example Assessment Tasks

- PYP Attitude Posters (printable)

- Publications

RSS Feed

RSS Feed