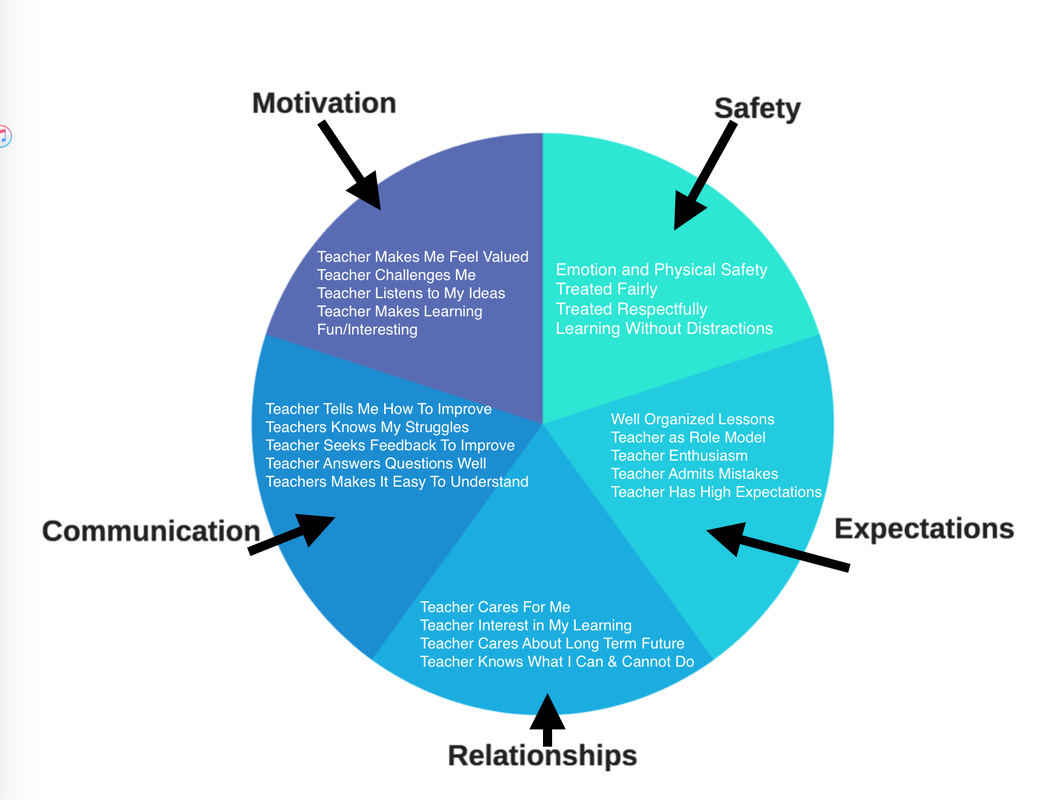

Finding Out What Students Really Think and Feel About Our TeachingOne of the most powerful avenues to self-improvement as a teacher involves accessing the voices of those who matter most — our students. When carefully planned out, student voice can be an extremely effective tool for helping to critically reflect upon our own teaching by using this data to inform next steps in regards to how we might improve upon our practice. All teachers in my current school are required to collect student voice throughout the year in order to identify needed areas of growth and development. Once this feedback is collected from the students, the teachers sit down with their pedagogical coordinators to analyze this data and to create their own action plan for improvement. The 5 areas that teachers can seek feedback on are; Expectations, Safety, Relationships, Communication, and Motivation. Each of these areas are further broken down into specific guiding statements related to that particular area as seen in the diagram below. Our school adopted this model from a well-known educational consulting agency from New Zealand. The company's name is Interlead and they have played an influential role in improving upon teacher practice at our school. I highly recommend checking out their work. In utilizing student voice in your program, not only will students know that what they think and feel truly matters, teachers have an opportunity to model what having a growth mindset looks like by taking action on the feedback received. Teachers can share the feedback with their students, identifying the areas that they have to get better at and how they are going to do this. Teachers can pick any of the above areas to receive feedback on and can collect it in whatever way they feel is best. Students are generally more inclined to respond honestly if an anonymous survey is given as they can sometimes worry that their responses might be used against them. In creating a culture of trust with your students, it is critical to let them know that you genuinely seek their honest feedback. Of course, many of you already understand this, but it is still important to be aware of.

1 Comment

What type of feedback do you seek the most in regards to your teaching practice? Photo coutesy of http://blog.clientheartbeat.com/customer-feedback-loops/ Photo coutesy of http://blog.clientheartbeat.com/customer-feedback-loops/ Over the past couple of years, I have experienced quite a steep learning curve in regards to my own professional learning journey. To this day, the most rewarding part of my career has been all of the years I taught physical education to my students. When I reflect back on the beginning of my career teaching PE, like many teachers new to the field of education, I had so much to learn. Having played competitive sport throughout high school and university, I placed great value on fitness training and exercise. Without question, this led to me setting up my physical education program in a way that reflected these strong values that I held. I believed that all kids needed to understand the value of sport and being fit. I blindly went about my days being driven by these values thus expecting my students to all embrace these values as well in physical education. I was the fitness testing king! From those early days of teaching physical education to the last day I taught PE at Nanjing International School in China in 2015, I put a tremendous amount of time and energy into my teaching practice. I always considered myself to be the type of teacher who sought feedback and used this feedback to put specific strategies into action that would help me continually improve my practice. I'm quite proud of the teacher that I became but, by no means, did I consider this journey complete. However, I now look at this journey through a different lens. In 2015-2016, I dove into a year of full-time consulting and had the good fortune of traveling around to various parts of the world, working with teachers, mostly in international schools, helping them to refine their teaching practice and re-design their physical education programs. This led to working with teachers beyond physical education in music, visual arts and classroom teachers. It was during this time that I started to see lots of variety in the way teachers delivered their lessons and units. Although many of these teachers were well-intentioned and had the best interest of their students at heart, I began to notice similar patterns in regards to a willingness, on their part, to address certain limitations or under developed areas of their teaching. That's not to say that the teachers I worked with were unwilling to learn, to grow and to develop their teaching skills, but what I did notice was that giving honest feedback was often met with an awkward silence that was boarder line quite uncomfortable at times. It made me reflect on my own ability to accept honest and genuine feedback when I was teaching. Was I more after praise and positive feedback when I was teaching or was I genuinely open to critical feedback of my practice? Was it easier for me to focus on my strengths and what I was doing well than actually digging into repetitive patterns in my teaching that might have held me back from being a better educator? The number one problem I could identify within myself when I reflected back on my own practice was my inability to depersonalize critical feedback . As I invested so much time and energy into my learning as a teacher, I placed a lot of pride in what I did. Our ability to depersonalize critical feedback can often be the number one culprit in holding us back from deeply improving upon our teaching practice. After a year of full-time consulting, I accepted a new role working as a Pedagogical Coordinator at the KAUST School in Saudi Arabia. A great opportunity to work with teachers helping them to improve their practice but through the specific lens of cognitive coaching. Cognitive coaching is rooted in the fundamental philosophy that there is greatness within all of us that can be unlocked by helping teachers tap into their internal resources. This model of coaching bases itself on assisting teachers with constructing specific data to be collected in regards to their teaching practice. This data is collected by the cognitive coach who observes the teacher in action with their students. Once the data is collected, the cognitive coach has a reflective conversation with the teacher seeking their perspective on how the lesson went. The data is then shared and discussed to support that teacher with identifying needed areas of development and potential strategies that could be applied to future teaching and learning to improve practice. Critical feedback becomes the responsibility of the teacher and the coach, but is easier done through the collection of data to support the teacher's growth. However, the reality is that most teachers don't have a cognitive coach, so this type of learning journey becomes a bit more difficult, yet in my opinion, not unattainable. The key is DATA!! Perhaps it's enlisting the support of a trusted colleague to come into your class and observe you teach. What you need to do is to think about key areas of your teaching you would like to know more about. These areas might include: Teacher Talk Time: How much time of your class is taken up with whole group discussions, giving instructions, or lecturing your students? (aim should be 20% total) Questioning: What types of questions are you asking your students? Deep or surface level? How long do you wait for responses? Are you asking open or closed ended questions? (both are OK depending on the situation) Engagement: To what extent are your students on track and engaged in the lesson? I'm certainly not trying to make this process sound easy, but it's worth tinkering with and seeing what type of data might be collected on your teaching. Once you receive this data, the big responsibility then is on your shoulders as to next steps that you might put into action depending on the results of the data. Some teachers do nothing with it after receiving it. Try not to go down this route. Everything I've discussed in this blog up to this point is all about teacher improvement and the willingness to be involved in a process that allows educators to work on their strengths but also address limitations as well. In a perfect world, ALL teachers would understand the value of feedback and the role that it plays in helping to genuinely improve upon our practice.

However, the reality is that many of us still operate in the sphere of wanting praise or positive feedback rather than critical feedback. It is human instinct to want to feel good, to be confirmed, and validated in regards to our work. Everyone of us wants to do a good job. A well-known 'change' consultant I know, recently shared his statistics in regards to the work he has done around the world in regards to helping educators/administrators improve upon their job performance. What he told me is that, based on his experience, somewhere around 70% of educators default to assuming feedback should be or needs to be positive and that less than 10% of teachers see critical feedback as being potentially useful. Hearing these statistics made me reflect more deeply on my own practice when I was teaching and to question how open I was to critical feedback. Although I feel I improved in this area my last few years of teaching, I still feel as though I was among the 70% of teachers defaulting to a stance that feedback should be positive. So, in closing off this blog post, I would like to ask any person reading this to reflect upon how you absorb critical feedback. Obviously, it's all in the way it is delivered, but even if delivered in a neutral, non-threatening manner, are you able to depersonalize this feedback and move forward in a way that allows you to genuinely embrace it in an effort to improve upon your practice. And lastly, I'm not implying there is no place for praise or positive feedback. Without question we all need it. However, to what extent do you balance the need for praise, yet accept and/or invite critical feedback into your professional practice. Happy teaching folks. Creating strong emotional hooks can inspire young learners in physical education. Through careful, well-thought out planning, a stimulating environment can be constructed that supports learning and development in PE. I'm very lucky to work with a number of very passionate PE teachers who commit themselves to creating warm and inviting learning spaces in their program. He recently taught an individual pursuits unit that had a specific focus on developing fundamental movement skills in the young kids that he teaches. Over a few planning sessions, Zack and I discussed different ways to create emotional hooks that would help to better engage the kids in this unit. He came up with the idea of having a super hero theme for the entire unit that would be rolled out in the first lesson. Throughout the unit, the students unpacked different super hero skills and explored those skills in a carefully designed space that Zack had set up.

As the unit progressed, Zack had students tune into what type of super hero they would like to be, what skills this super hero possessed, and how they might work to develop these skills. I observed several classes and collected data on the level of engagement and focus the kids showed. It was clear to see that the students were all very engaged and thoroughly enjoying the unit. As the kids are quite young, they of course needed reminders to stay on track and to be re-directed at times, but the data showed that many of the students remained on task for most of the 30-minute class. This was consistent over a number of classes that I had observed Zack's students. As a culmination to the unit, Zack had the kids dress up as super heroes and showcase their talent on the final day. He even sent a letter home to parents encouraging them to allow their kids to come to school dressed as super heroes! Zack kept the classroom teachers in the loop by informing them of what was happening in his unit, so they were fully aware of the plan for the final day. In the last class of the unit, the atmosphere was buzzing as students had free exploration of different stations that had been set up. There was tumbling, jumping, throwing, rolling, balance beam walking, and leaping from tall buildings (the tall building being a stack of mats!). Zack had an assessment set up that allowed him to see each student's super hero skills. It was pure joy in motion. When teaching early years students, how do you structure your environment to help create those strong emotional hooks for your students? How do you use story and provocation to capture their interest and immerse them in the unit? Would love to hear your thoughts. Thanks for reading. If you are an early years teachers, I recommend connecting with Zack Smith as he has lots of great ideas and resources to share. |

AuthorKAUST Faculty, Pedagogical Coach. Presenter & Workshop Leader.IB Educator. #RunYourLife podcast host. Archives

September 2022

|

- Welcome

- All Things Teaching and Learning

- The Aligned Leader Blog

- Consulting and Coaching Opportunities

- My TED X Talk

- My Leadership Blog

- Run Your Life Podcast Series

- How PYP PE with Andy Has Helped Others

- Good Teaching is L.I.F.E

- The Sportfolio

- Example Assessment Tasks

- PYP Attitude Posters (printable)

- Publications

RSS Feed

RSS Feed